Divining the life stories of native North Americans who lived thousands of years ago but left no written records requires a unique blend of the social and life sciences. Thanks to a wealth of new data they’ve uncovered in recent years, and new techniques for extracting meaning from their findings, researchers at Binghamton University’s Public Archaeology Facility (PAF) are rewriting some of the most widely accepted theories about prehistoric life in New York state.

Much of the new information used by PAF archaeologists has resulted from cultural

resource management investigations for

economic development projects across New

York state (see sidebar).

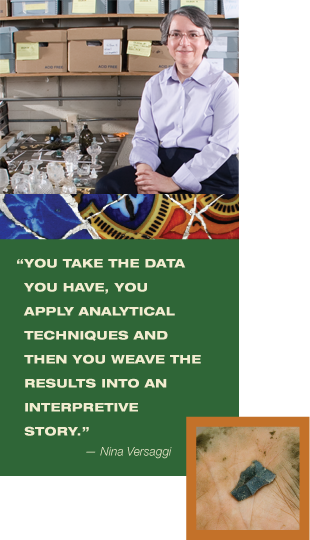

Culling valuable data from ancient objects — stone tools, brokenpottery, a few seeds, the remains of a hearth — archaeologists piece together a tableau of people who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago. “You take the data you have, you apply analytical techniques and then you weave the results into an interpretive story,” said Nina Versaggi, PAF director.

As PAF personnel discover new sites and apply more powerful analytical techniques, their interpretations of ancient diet, community organization, division of labor and group dynamics within our valley systems become more complex. However, these interpretations are not static. “Somebody 20 years from now will be able to re-analyze the same data with new analytical tools and add to the story,” Versaggi said.

For now, though, based on the work of the PAF, the story that is beginning to emerge about life here before Europeans arrived is more detailed and more complex than any version that archaeologists have subscribed to in the past.

Chronological sequences are one example. For a long time, Versaggi explained, archaeologists maintained that changes in prehistoric technology (tools and how they were made),“foodways,” or means of accruing sustenance (foraging vs. farming) and settlement patterns (seasonal movements vs. year-round villages) occurred at the same time everywhere across the region that now contains New York state. For example, traditional chronological models stated that people changed the shape of their hunting tools or projectile points, replaced stone bowls with clay pots and began to plant domesticated species of maize, beans and squash according to an established temporal framework.

Archaeologists in the early to middle 20th century based these chronologies on data collected from a small number of deep, well-stratified sites. “Researchers accepted these chronologies as fact and adhered to them for decades,” Versaggi said. “They were used by us, and they’re still used by archaeologists today. They’re not invalid. But they tend to hide a wealth of variability that could be related to cultural and ethnic differences among prehistoric peoples.

New analytical techniques have assisted the process of discovery and interpretation.For example, a new method of radiometric dating, Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS), has become more accessible and affordable, allowing the facility’s teams to obtain a greater sample of dates from a larger number of sites than archaeologists did in the past. Sometimes, these new dates show that sites with certain artifact types do not agree with the traditional chronologies. This suggests that the boundaries between cultural periods aren’t as precise as scientists once thought. “We’re finding there are regional differences, and we’re finding these may be related to cultural differences,” Versaggi said.

For example, early archaeological research showed that at about AD 1000, people living on the lakeplain surrounding Lake Ontario started forming larger villages and going through rapid cultural change, Versaggi said. The ease of travel from the St. Lawrence Valley through the Great Lakes into the Midwest provided opportunities for people and ideas to travel over great distances. Some of these changes included a great deal of innovation in pottery design and decoration. But on the Allegheny Plateau — which includes New York’s Southern Tier — the terrain is more rugged, and water travel is oriented north-south rather than east-west via rivers, such as the Susquehanna, Delaware and Allegany. Villages in this region were smaller, and people probably did not have the same degree of interaction as the northern groups had. “So, certain aspects of material culture, such as pottery traditions, did not change at the same rate,” Versaggi explained.

This interpretation emerged when doctoral students Laurie Miroff and Tim Knapp (also PAF researchers) obtained a large number of AMS dates from carbon associated with decorated pottery at the Thomas/Luckey site in the Chemung River valley. The dates suggested that certain types of decorated pottery persisted for about 100 years past the point traditional chronologies dictated. “Maybe 20 or 30 years ago, we would have said, ‘Our dates are incorrect due to contaminated carbon,’”Versaggi said. “But now we are building a body of evidence that supports an interpretation of how people interacted with each other, and how change was incorporated into their social structures.

”On a similar note, traditional chronologies based on a few sites on the Ontario lakeplain marked a time around 1000 BC when people stopped using bowls made of steatite — also called soapstone — and started using clay pottery. However, PAF’s Versaggi and Knapp have found that people in the valleys of the Southern Tier continued to use soapstone bowls, possibly alongside clay pottery, during periods that ranged from 900 BC to 200 BC.

page 1 | page 2